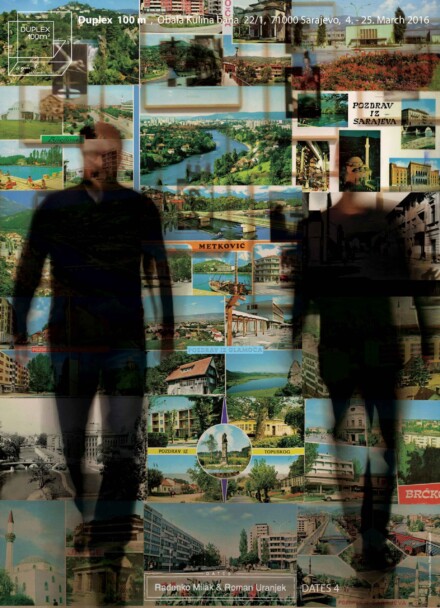

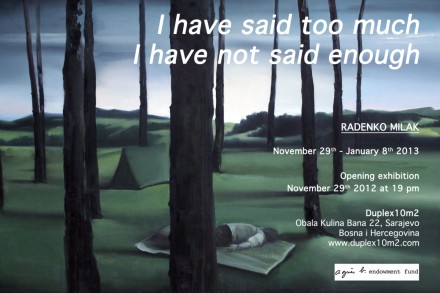

Radenko Milak 2012

«I have said too much, I have said enough»

« The painting of Radenko Milak » by Jon Blackwood – Sarajevo Culture Bureau

Radenko Milak’s show of new paintings and watercolours opened about ten days ago now at duplex, and it is an intriguing exhibition full of subtleties and wry political and historical observations. Art History is littered with examples of critics or arts administrators who were not quite so good as painters (Roger Fry, Adrian Heath, Miodrag B. Protić) but Milak, head of the PROTOK artists’ organisation in Banja Luka, is certainly not a name for that list.

In the duplex corridor we find the watercolour series Borders of 2012. This is a rather monochrome series full of new uncertainties. At the best of times, borders are a grey, cheerless, bureaucratic zones, somewhere to be got through as quickly as possible. In this series however, Milak conveys the slight tinge of fear and the uncertainty of the new with the seemingly endless erection of new borders across former Yugoslavia in the last twenty years. A red Lada Zhiguli trundles slowly towards the viewer from a grey and depopulated landscape; all the tension in these unsettling little compositions is held in the silhouetted outline of the figure just beyond our space and behind the picture plane; As viewers, we are left in the same state of awkwardness as the car driver as he prepares for the encounter with the faceless, armed official; will this strange new border be crossed without incident, or will many hours and much money have to be spent before the invisible line can be crossed- indeed, will it be crossed at all?

Many of the paintings here are open ended and ambiguous, inviting the viewer to compare possible endings. In this sense, Milak invites the viewer to join with him in trying to resolve the uncertain narratives presented. Take, for example, the large scale work in oil Big Time, the newest painting on display. This is a timeless painting, set in an uncertain period. The colour and composition are tightly controlled; the palette is restricted to dull green and grey; unlike in the Flags series, there is no sensory appeal here. A figure lies slumped on a blanket in the middle ground, with his tent slightly behind; is he just resting, or dead? It is impossible to tell. The recognisable landscape of BiH, completed almost in the manner of a stage-set, is presented in two ways; as a beautiful place in which to enjoy leisure, a beauty counteracted and tarnished by a long history of sudden violence, murder and death. Milak’s paintings are understatedly bittersweet; deliberately unsettling a sense of the normal and banal through small details and murky painterly depths.

Perhaps the most powerful series is the pencil and watercolour portraits, Body Language, fourteen in total, and a sequence of works still in development. The subject is the notorious Ratko Mladić, whose long career as a fugitive after the Bosnian war, subsequent arrest and recent arraignment before the ICTY in the Hague, have been such a livid and controversial thread in the history of BiH. Milak offers little comment on Mladić himself, but seeks to approach him almost in experimental terms, exploiting the forensic gaze of the international court to portray Mladić in different moods; defiant, contemptuous, uncertain, bored. Much in the manner of Sarah Vanagt’s rubbings of the defendants’ desk at the ICTY, exhibited at duplex in November, Milak seeks to approach Mladić through the banal and the commonplace, in order to try and provide a closer look at him. The trapping of particular flickers of the eyes, sets of the jaw, and gestures of the hands in this series are the means through which he provides a psychological portrait of this man.

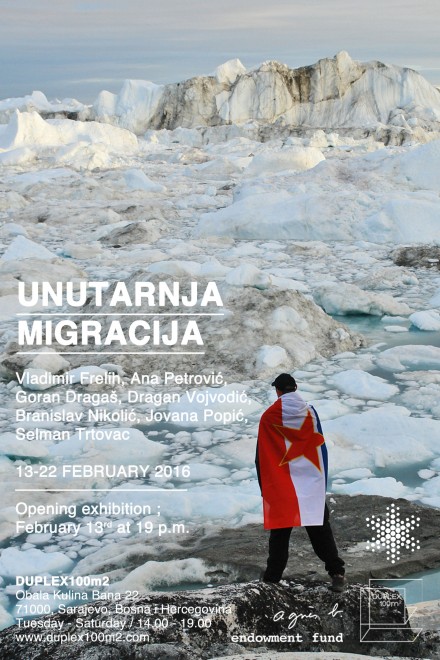

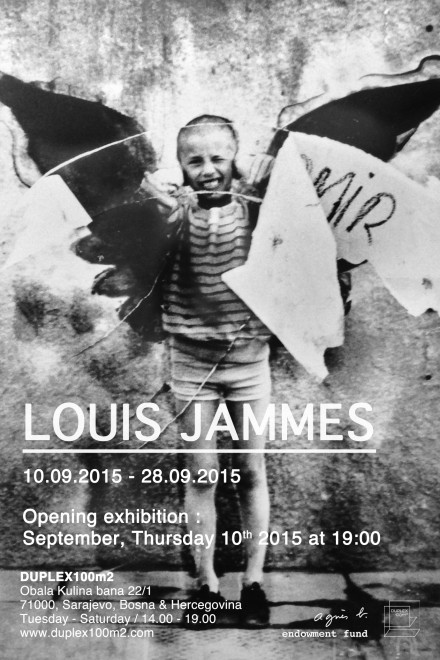

The watercolour series Flags employs a similar method. Here, the psychological focus is not on individuals, but in how whole groups of people willingly buy into the mythical narratives of nationhood as represented by pieces of coloured cloth; and subsume their own priorities and preferences in the name of this myth. This bizarre process, so corrosive in this part of the world, is presented through many different small vignettes; in the example above, typically, the colours of the flag are livid and luminous, reducing the appearance of the individual to that of a cypher, a puppet. The same composition is employed across this series of works, from the Greek football fans burning the Bosnian flag in the recent international in Athens, to the Albanian paramilitary holding the red and black flag alongside the Stars and Stripes, mounted on horseback. In each of the paintings, the handling of the colour and the landscape recalls late nineteenth century realism. In those paintings, however, typically of agricultural labour (I am thinking of Courbet, Bastien Lepage, James Guthrie) the character and experience of the individual is paramount in understanding the priority of these paintings; this is a kind of twisted twenty first century Balkan realism, where the equation is inverted; the individual matters much less than the arbitrary and contingent symbol that they identify themselves with.

Ultimately, the strength of this exhibition lies not only in Milak’s very assured control of the differing mediums that he chooses to work in, but in holding up a mirror to historical and political developments in South-Eastern Europe in the last two decades.

For people who lived here or in exile through the traumatic wars and subsequent anarchic period of transition, these are very familiar. But, to present these events again and to have an audience re-consider the familiar, to subtly prompt the individual to think again and re-examine their recollections and fixed perceptions, is surely all that one can ask of a painter. In this task, Milak has achieved a major success in this show, and the exciting thing about him is that he has still so much room to develop further. That will be a very interesting process to watch in the years to come.