WHO NEEDS DRNČ

Adela Jušić

Video work Snajperist (engl. sniper) originates from my attempt to face my wartime childhood and the greatest loss I experienced then – losing my father.

The aggressor’s sniper campaign against the population of the besieged Sarajevo during the last war was an inhuman violation of the rules or customs of war directed principally towards civilians.

My father has been a member the BiH Army from the outset of the war through 3 December 1992 when, as a sniper, he was given a combat assignment to neutralize the enemy sniper soldier. He penetrated the enemy territory courageously and that’s where he was killed by a sniper bullet which hit him in the eye.

Right before his death I found his notebook into which he continuously, over those several months, listed how many soldiers he had killed during his combat assignments.

In this work I am trying to reconstruct the memory of the numbers from the notebook, and through that process and through my relationship with my father the soldier, and above all, to confront with the trauma brought to me by his death. In this kind of confrontation the whole process of research about the moment of my father’s death was extremely important to me, in the course of which I spoke to the family members, his fellow soldiers, and finally, with the man who managed to bring his body out from the enemy territory twelve hours after his death. It turns out that my family’s confrontation with my work is no less important, as I’m still trying to find enough courage to show my work to my mother. Watching this video time and time again, I’ve noticed it has an equally emotional impact on me as it did one year ago, although now I can more easier and more often decide to watch it. When it was first finished, I honestly avoided to take a look at it, but I also avoided presenting the work to the audience. It was especially difficult for me to watch this video in the presence of others.

It was essential for me to realize this work, for by finally visualizing my trauma, I am getting the opportunity to summon it to a duel any time I wish to.

The video work entitled Kome treba drnč results from the logical course of emotions connected to my wartime childhood and my relationship with my father who was a soldier in that war.

This is an attempt to recall the happiest moments from within that relationship and to try and explore them in the framework of my memories and emotions, but also in the framework of the emotional and the rational as seen from the aspect of this day.

When my father would return from the battlefield all worn out, he’d have me clean his weapons. I couldn’t be more happy. For me his rifle was inseparable from his figure, since my experience of my father was, and still remains, strongly intertwined with his identity of a soldier.

Hence my visual, but also every other possible kind of memory of my father, are explicitly related to the war, the uniform, dirty boots, weapons, courage... He is primarily not father, but my father-soldier, who keeps coming and going, and every time he leaves, I am afraid he won’t be back. Those two identities of his were for me even more inseparable considering that I had been experiencing the happiest moments of our father-daughter relationship during those very moments of me cleaning his weapons. During these moments the father was proud of his daughter, and the daughter was aware of it, and this meant to her much more than any kind of hug or word.

Then he would leave to battle again, and he’d come back, and our family ritual would be repeated.

By discussing this work with my close fellows who survived the war in Bosnia I realized that such a relationship with one’s father was not a distinct case, although I had long entertained such thoughts. On the contrary, this was a relationship quite common in the families of the time, dominated by the wartime family ritual which linked the father and the child in a completely unusual manner, in a way only war can link people and within any other relationship in the society.

I’ve also noticed that the rituals of cleaning the rifle of one’s father-, and sometimes even one’s mother-soldier, are marked in the memories of those then-children, nowadays already mature people, as moments of intimacy and family idyll.

The work’s title Kome treba drnč resulted from my conversation with my father’s brother: “You have got no drnč, and we didn’t have any during the war either”, he said. That’s how I learned that for cleaning weapons one needs drnč, a solvent intended only for cleaning and not for oiling, and that this was an old expression used in the Yugoslav National Army. During the war in Bosnia, the aggressor army naturally had large quantities of drnč which originated from the Yugoslav National Army’s reserves, while the soldiers in the BiH Army, and in many other war situations, used alternative means.

Drnč /drnch/ (Bosnian) noun from abbr. “Deterdžentni rastvarač naslaga čađi” detergent solvent of soot layers, a type of weapon cleaner.

In the further discussions with the BiH Army soldiers I notice how upon the very mention of drnč I could get various answers: some of them have heard about this solvent, although they cleaned their weapons regularly, while some others have heard of it but never had the opportunity to use it. The rare ones bragged about the several occasions on which they cleaned their rifle with drnč, and one former soldier showed me his bayonet and said: “Smell it, for this is the real drnč”. He was so proud for being able to share that smell with me. The smell was a total news for me too.

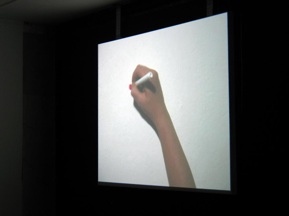

In my search for a rifle to clean I turned to many army officials. Finally, some modern sniper was promised to me, and meanwhile a completely unpredicted event took place: in my house I discovered an old war rifle M-64.

It is totally rusty and really isn’t so representative. I decide then to forget about cleaning the promised modern sniper and to use for my work that old AK-48 which brought back with itself the true energy of the past war.

While preparing the rifle for this work I rekindled the pleasant moments spent wit my father. I learned again how to dismantle and put back together a piece of weapon, and I spent days rehearsing the process. The rifle in this context entirely loses the role which the very nature of such object assigns to it as primary. It is dismantled, and put together again, cleaned and oiled, but not in order to fire. Now it is just a toy in my hands calling back for childhood.

KOME TREBA DRNČ

Adela Jušić

Video rad „Snajperist“ nastao je kao pokušaj da se suočim sa svojim ratnim djetinjstvom i sa najvećim gubitkom koji sam tada doživjela, a to je gubitak oca.

Snajperska kampanja koju je agresor vodio nad stanovništvom u opkoljenom Sarajevu u periodu proteklog rata bila je nehumana i usmjerena, suprotno običajima ratovanja, prije svega prema civilima.

Moj otac je bio pripadnik Armije BiH od početka rata, pa sve do 3.decembra 1992.godine, kada je kao snajperista dobio borbeni zadatak da neutrališe snajperistu neprijateljske vojske. Hrabro je ušao u neprijateljsku teritoriju i tu je ubijen snajperskim metkom koji ga je pogodio u oko.

Neposredno pred njegovu smrt, pronašla sam notes u koji je, u kontinuitetu od nekoliko mjeseci, bilježio koliko je vojnika ubio tokom svojih borbenih zadataka.

U ovom radu pokušavam rekonstruisati sjećanje na brojke iz notesa, te kroz to i svoj odnos prema ocu vojniku i, prije svega, suočiti se sa traumom koju je donijela njegova smrt. U takvom suočavanju neizmjerno mi je bio bitan kompletan proces istraživanja o momentu očeve smrti tokom kojeg sam razgovarala sa članovima porodice, njegovim saborcima i konačno sa čovjekom koji je njegovo tijelo uspio izvući iz neprijateljske teritorije12 sati nakon smrti. Ispostavilo se da ništa manje nije bitno ni suočavanje moje porodice sa radom, jer još uvijek pokušavam iznaći dovoljno hrabrosti da svoj rad pokažem majci. Gledajući svaki put iznova ovaj video, primjećujem da na mene djeluje podjednako emotivno kao i prije godinu dana, mada se sada lakše i češće mogu odlučiti da ga pogledam. Kada je tek završen, zaista sam izbjegavala da ga gledam, ali i sam izbjegavala i prezentaciju rada publici. Naročito mi je bilo teško gledati ovaj video u društvu drugih.

Realizirati ovaj rad za mene je bilo neophodno, jer konačno vizualizirajući svoju traumu, imam priliku da je pozovem na dvoboj kada god to zaželim.

Video rad „Kome trebe drnč“ nastao je nakon „Snajperiste“ kao logičan slijed emocija koje su vezane za moje ratno djetinjstvo i odnos sa ocem koji je bio vojnik tog rata.

Pokušaj je da prizovem najsretnije momente unutar tog odnosa i da ih istražim u okviru svojih sjećanja i emocija, ali i u okviru emotivnog i racionalnog sa današnje tačke gledišta.

Kada bi moj otac umoran dolazio sa ratišta, davao bi mi svoje oružje da ga očistim. Mojoj sreći nije bilo kraja. Za mene je njegova puška bila nerazdvojna od njegovog lika, jer je moj doživljaj oca bio i do danas ostao snažno vezan za njegov identitet vojnika.

Dakle, moja vizualna ali i svaka moguća vrsta sjećanja na oca vezana su isključivo za rat, uniformu, prljave čizme, oružje, hrabrost...On nije prvenstveno moj otac, već moj otac-vojnik, koji stalno dolazi i odlazi, i svaki put kada ode, ja se bojim da se neće vratiti. Ta dva njegova identiteta za mene su nerazdvojna utoliko više što sam najsretnije momente našeg otac-kći odnosa doživljavala upravo čisteći njegovo oružje. U tim trenucima otac je bio ponosan na svoju kći, a kći je toga bila svjesna i to joj je značilo više od bilo kakvog zagrljaja ili riječi. Zatim bi opet odlazio u borbu i vraćao se, a naš porodični ritual bi se ponavljao.

Razgovarajući o tom radu sa bliskim vrašnjacima koji su u Bosni preživjeli rat, shvatila sam da ovakav moj odnos sa ocem nije bio usamljeni slučaj, iako sam dugo tako mislila. Naprotiv, bio je to u porodicama čest odnos u okviru kojeg je dakle, dominirao ratni porodični ritual koji je povezivao oca i dijete na potpuno neuobičajen način, onako kako to samo rat može povezati ljude i unutar bilo kojih drugih odnosa u društvu.

Primijetila sam takođe da su rituali čišćenja puške ocu, te ponekad čak i majci vojniku u sjećanjima tih danas već odraslih ljudi ostali zabilježeni kao trenuci bliskosti i porodične idile.

Naziv rada „Kome treba drnč“ nastao je nakon razgovora sa očevim bratom.:„Nemaš drnča, ali ni u ratu ga nismo imali“, rekao mi je on. Saznala sam tako da je za čićenje oružja potrebnan drnč, sredstvo koje služi isključivo čišćenju, a ne podmazivanju, te da je to stari izraz koji se koristio u JNA. U toku rata u BiH, agresorska vojska je naravno imala velike količine drnča koje su poticale iz rezervi JNA, dok su vojnici Armije BiH, kao i u mnogim drugim ratnim situacijama, koristili alternativna sredstva.

Razgovaravši dalje s borcima Armije BiH primijetila sam kako na pomen drnča dobivam različite odgovore: neki uopšte nisu čuli za ovo sredstvo, iako su svoju pušku redovno čistili, dok drugi jesu, ali ga nikad nisu imali priliku koristiti. Rijetki su se pohvalili da su nekoliko puta svoju pušku očistili drnčem, a jedan bivši vojnik mi je pokazao svoj bajonet i rekao: „Pomiriši, e to ti je pravi drnč“. Bio je ponosan što sa mnom može podijeliti taj miris. Miris je i za mene bio potpuno nov.

U potrazi za puškom koju ću čistiti obratila sam se mnogim vojnim dužnosnicima.

Konačno, obećan mi je nekakav moderni snajper, međutim, desila se potpuno nepredviđena stvar: u svojoj kući ja otkrivam staru ratnu pušku M-64.

Ona je potpuno zahrđala i zaista nije reprezentativna. Odlučujem zaboraviti na čišćenje obećanog modernog snajpera i za svoj rad iskoristiti stari AK-48 koji u sebi nosi istinsku energiju rata.

Pripremajući pušku za ovaj video rad oživjela sam lijepe trenutke provedene sa ocem. Učila sam ponovo kako rastaviti i sastaviti oružje i provela dane vježbajući taj proces. Puška u ovom kontekstu potpuno gubi ulogu koja joj je po prirodi samog predmeta primarna. Ona je rastavljena i sastavljena opet, očišćena i podmazana, ali ne zato da bi pucala. Sada je samo igračka u mojim rukama koja priziva djetinjstvo.

Adela Jušić, Rođena 20.10.1982. godine u Sarajevu, gdje je završila Srednju školu primijenjenih umjetnosti i Akademiju likovnih umjetnosti, odsjek grafika.Živi i radi u Sarajevu. Pored grafike, bavi se video artom već nekoliko godina. Imala je dvije samostalne izložbe „Jedan puta jedan jednako dva“ , iz ciklusa grafika „Autoportreti“ ARTATAK / SCCA, So.Ba, Sarajevo, 2007. i „Kome treba DRNČ“, Galerija 10 m2, Sarajevo, 2008., te je u proteklih godinu dana učestvovala u grupnim izložbama : Međunarodna godišnja izložba savremene umjetnosti Spa Port, kustosica Ana Nikitović, Banja Luka, „One lično“, kustosica Branka Vujanović, Zenica, Bihać, Sarajevo, Festival ženske umjetnosti “PitchWise”, Sarajevo, „Video-box 3“,Galerija 10m2, Sarajevo, Šesti festival kratkog filma, Mostar, Festival „Dani Sarajeva“, Beograd, Balkan Express vol 2, Galerija Pixel Art, Varšava.

PHOTO